The Essential Films

A blog devoted to the discussion of the greatest movies ever made, or The Essential Films. From the beginning of cinema history to present day, these films are crucial to the education of anyone who loves the art of film making.

Tuesday, April 29, 2025

Wednesday, November 13, 2024

Dracula (1931)

and audiences alike. Executives were nervous about the box office potential of a film with a heavy reliance on the supernatural. After its premiere, newspapers reported that some audience members fainted at the site of the images on screen. Publicity jackpot. The studio wisely used this to sell the film in advertisements and it became a big financial success. Because of the success of Dracula, Universal plunged headfirst into the horror waters and produced a series of successful monster movies: Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and The Wolf Man (1941) as well as a string of sequels: Dracula's Daughter (1936), Son of Dracula (1943), House of Dracula (1945) and Dracula made appearances in House of Frankenstein (1944) and the afore-mentioned Abbot and Costello crossover. Dracula's legacy, much like the vampire himself, will live forever. To this day, fans of horror everywhere celebrate the "Universal Monsters."

- National Film Registry: Class of 2000 Inductee

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – #85

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains: Count Dracula – #33 Villain

Friday, October 18, 2024

HALLOWEEN (1978)

1978 • John Carpenter

was originally a William Shatner/Captain Kirk rubber mask painted white, became an iconic symbol of death, deeply rooted in its simplicity and the uncanny effect it produces. Unlike masks with exaggerated features or grotesque expressions, the blank, featureless visage of the Myers mask creates an unsettling aura of ambiguity and emptiness. It's a canvas devoid of emotion that conceals the malevolence within. The absence of facial expressions robs the audience of any cues to understand or empathize with the character. Human faces are the primary way we connect with others, read their emotions, and gauge their intentions. When a face is devoid of these signals, it is profoundly disconcerting. This absence of identity amplifies the fear and Michael becomes an enigma, a shape (if you will) lacking any humanity, and therefore, an entity beyond comprehension. The contrast between the mask’s emptiness and the brutality of his deeds accentuates the horror.

Thursday, September 26, 2024

Sunday, September 22, 2024

I Wrote a Book!

Tuesday, August 27, 2024

NORTH BY NORTHWEST *Reaction & Commentary!*

Saturday, June 8, 2024

Tuesday, April 16, 2024

Freaks (1932)

Tuesday, February 27, 2024

3 DAYS OF THE CONDOR (1975)

3 DAYS OF THE CONDOR

1975 • Sydney Pollack

Screenplay: Lorenzo Semple Jr., David Rayfiel; Based on Six Days of the Condor by James Grady

Producer: Stanley Schneider

Cast: Robert Redford, Faye Dunaway, Cliff Robertson, Max von Sydow

Cinematography: Owen Roizman

Music: Don Guidice

Paramount Pictures

I don't interest myself in "why". I think more often in terms of "when", sometimes "where"; always "how much".

Grab your tinfoil hats and get ready to dive headfirst into the thrilling world of 1970s paranoia with 3 Days of the Condor. This film takes us on a rollercoaster ride filled with conspiracy, danger, and a dash of CIA antics. It takes us on a journey where trust is scarce, and everyone is potentially a double agent. Exciting, right?

It's 1975, and the world is knee-deep in Cold War tensions and cloak-and-dagger shenanigans. Our protagonist, played by Robert Redford, is a mild-mannered CIA analyst who spends his days diving into books, looking for hidden meanings and secret codes.

One day, Redford's character stumbles upon a sinister discovery. He finds out that his fellow co-workershave been brutally murdered. Suddenly, he finds himself thrust into a web of intrigue and danger, desperately trying to uncover the truth behind the conspiracy before it's curtains for him too. Let's just say it's a good thing he's got those CIA skills up his sleeve.

As Redford's character digs deeper, he realizes that he can trust no one. Everyone is suspicious. The office intern? Probably a double agent. The mailman? Definitely hiding some secret documents in those mailbags. Even the office vending machine might be keeping tabs on him. Paranoia at its finest.

Let's not forget the technical achievements of this gem either. Nominated for an Academy Award for Best Film Editing, it's clear that the masterful editing played a pivotal role in creating the suspense and tension that keeps you on the edge of your seat. Audiences appreciated this film as well, raking in a cool $41 million at the box office, which would be about $240 million in 2023 money. Not too shabby for a bunch of spy games and cloak-and-dagger antics.

3 Days of the Condor is a must-watch for fans of 70s paranoia thrillers, secret agent escapades, and those who just can't resist a good conspiracy theory. With its gripping plot, snappy dialogue, and some killer performances, this film will have you questioning everyone you meet for at least a week.

It will happen this way. You may be walking. Maybe the first sunny day of the spring. And a car will slow beside you, and a door will open, and someone you know, maybe even trust, will get out of the car. And he will smile, a becoming smile. But he will leave open the door of the car and offer to give you a lift.

Notable Awards & Accomplishments

• Academy Award Nominee: Best Film Editing

• Golden Globe Nominee: Best Actress - Drama: Faye Dunaway

• 6th Highest Grossing Film of 1975

Availability: Digital, 4K, Blu-Ray, DVD

Wednesday, February 21, 2024

Let the Right One In (2008)

The violence portrayed in Let the Right One In serves as a stark contrast to the tender friendship between Eli and Oskar, highlighting the weird nature of their relationship and the world they live in. On one hand, the violence in the film is a visceral reminder of the harsh realities of their existence. As a vampire, Eli needs human blood to survive, leading to grisly and brutal scenes where she hunts her prey. At the same time, the violence serves as a catalyst for the development of Eli and Oskar's bond. Oskar, who is himself a victim of bullying and violence, finds solace in Eli's companionship. Despite her predatory nature, Eli offers him a sense of understanding and acceptance that he struggles to find elsewhere. Their friendship becomes a refuge from the cruelty of the outside world. It challenges conventional notions of morality and empathy.

The violence portrayed in Let the Right One In serves as a stark contrast to the tender friendship between Eli and Oskar, highlighting the weird nature of their relationship and the world they live in. On one hand, the violence in the film is a visceral reminder of the harsh realities of their existence. As a vampire, Eli needs human blood to survive, leading to grisly and brutal scenes where she hunts her prey. At the same time, the violence serves as a catalyst for the development of Eli and Oskar's bond. Oskar, who is himself a victim of bullying and violence, finds solace in Eli's companionship. Despite her predatory nature, Eli offers him a sense of understanding and acceptance that he struggles to find elsewhere. Their friendship becomes a refuge from the cruelty of the outside world. It challenges conventional notions of morality and empathy.Friday, February 2, 2024

PAN'S LABYRINTH (2006)

PAN’S LABYRINTH

(El laberinto del fauno)

2006 • Guillermo del ToroCast: Ivana Baquero, Sergi López, Maribel Verdú, Doug Jones, Ariadna Gil, Álex Angulo, Pablo Adán

Screenplay: Guillermo del Toro

Cinematography: Guillermo Navarro

Music: Javier Navarrete

Warner Bros. Pictures

A long time ago, in the underground realm, where there are no lies or pain, there lived a Princess who dreamed of the human world.

Fascist Spain. 1944. Imaginative and aloof Ofelia is the young stepdaughter of the sadistic Spanish army Captain Vidal. Ofelia and her pregnant mother are brought in to live with Vidal while he finishes killing off the last of the rebel soldiers. Ofelia hates living under the tyrannical parental authority of her new stepfather and in an effort to distance herself from his cruelty, she escapes into a world of fantasy. Ofelia stumbles upon an ancient faun living in a labyrinth outside her new home. He tells her she has to perform three tasks and she will become a princess of a magical kingdom. Definitely not for children, Pan's Labyrinth is a film that pays homage to children’s fairytales and films like Alice in Wonderland and The Wizard of Oz. But is it all really happening, or is it all in Ofelia's vivid imagination?

It is a seemingly straightforward fantasy plot that is in actuality rich in its depth and complexity. While it follows the journey of Ofelia into a fantastical labyrinth, it forces us to confront the harsh truths and brutalities of the world while also delving into the power of imagination and resilience in the face of adversity. Guillermo del Toro invites audiences to contemplate the blurred lines between reality and fantasy, innocence and brutality, leaving a lasting impact on you.

Pan’s Labyrinth masterfully intertwines two parallel narratives: a magical quest and a political war drama. Del Toro skillfully balances these contrasting worlds, seamlessly shifting between the enchantment of Ofelia's quest and the grim horrors of a war-torn society. As the fantastical and the grim reality converge, Pan's Labyrinth explores themes of resilience, sacrifice, and the enduring human spirit amidst the tumultuous backdrop of Francoist Spain.

A beautiful lullaby bookends the film called "Long, Long Time Ago" ("Hace tiempo, mucho tiempo" in Spanish). It was composed by, Javier Navarrete, who also composed the film's entire score. The haunting melody of the lullaby adds to the film's ethereal and melancholic atmosphere, capturing the essence of Ofelia's journey and the film's themes of innocence and loss. It is sung by Mercedes, the housekeeper (and secret rebel collaborator), and while it is the same soulful song, it evokes different moods. In the beginning, it serves as a “Once upon a time,” with its sense of nostalgia. At the end of the film, it is different. It almost serves as a “and they lived bittersweetly ever after,” but with a sense of longing and sadness.

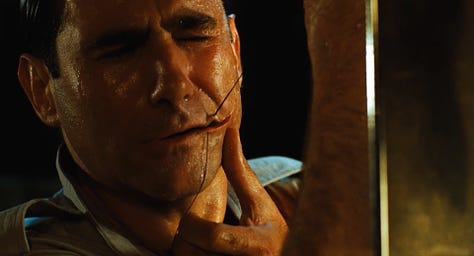

Sergi López delivers an amazing villainous performance as Captain Vidal, the not-so-subtle metaphorical stand-in for Francisco Franco. Vidal embodies the epitome of a well-groomed gentleman, meticulously attending to his appearance by personally shaving and shining his boots, reflecting his meticulous attention to detail and obsession with control. Despite his outward facade of military perfection, Vidal harbors a monstrous and sadistic nature, a trait he conceals beneath a veneer of unemotional detachment. As a brutal Falangist Captain, Vidal ruthlessly pursues his mission to eradicate leftists from the hills of Northern Spain, embodying the authoritarianism and violence of Francoist Spain. Sergi López's portrayal of Vidal captures the chilling duality of a man who presents himself as a model officer while harboring a dark and evil interior.

Ivana Baquero delivers a remarkable performance as Ofelia. At just 12 years old, Baquero portrays Ofelia with maturity beyond her years while capturing a sense of Alice-like wonder. Ofelia's journey into the labyrinth unfolds as she encounters a host of mystical creatures and challenges laid before her. Ofelia is innocent, but brave and determined. You root for her to triumph against the dark forces that threaten her world. While the creatures pose their own challenges and mysteries, it is Captain Vidal's menacing presence and violent nature that truly terrify Ofelia. Ofelia understands the very real dangers posed by Vidal and the oppressive regime he represents. His cruelty towards those he perceives as enemies, including herself, instills a deep sense of dread and apprehension in Ofelia.

But perhaps she should be more careful. One of the compelling aspects of the film is the ambiguity surrounding the character of the Faun. Throughout the film, the Faun serves as a mysterious and enigmatic figure who guides Ofelia on her journey, presenting her with tasks and challenges that test her courage and resolve. However, the Faun's motives and intentions remain shrouded in mystery. On one hand, the Faun offers Ofelia the promise of reclaiming her identity as the princess of the underworld, leading her to believe in a destiny beyond the confines of her mundane existence. On the other hand, the Faun's methods are often cryptic and ambiguous, and his demands for obedience and sacrifice raise doubts about his true nature. By the end, we get a definitive answer… or do we?

One of the lingering questions you may have when the credits role is: Is the quest an imaginative coping mechanism for Ofelia? Did any of it actually happen? Is it like Alice in Wonderland or The Wizard of Oz, was it all just dreams and imagination? It's widely interpreted that Ofelia's quest is indeed an imagined escape from the brutality and hopelessness of her situation. By embracing the role of the underworld princess and undertaking the tasks assigned to her by the Faun, Ofelia can assert her identity and assert control over her own life. I, myself, choose to believe the fantasy. However, what makes the film great is that both interpretations are valid.

Life isn't like your fairy tales. The world is a cruel place. And you'll learn that, even if it hurts.

Notable Awards & Accomplishments

Academy Award Nominee: Best Writing, Original Screenplay

Academy Award Winner: Best Achievement in Cinematography

Academy Award Winner: Best Achievement in Art Direction

Streaming: Not currently streaming

Digital Rental/Purchase: Available at major digital retailers

Physical Media: Available on 4K, Blu-Ray and DVD